The new Digital Power China (DPC) report is out now: "Reverse Dependency: Making Europe’s Digital Technological Strengths Indispensable to China"

Despite Europe's efforts to reduce tech dependencies on China it will continue to rely on China. The tech ecosystems are too interwoven. Therefore, Europe needs to keep China reliant on Europe too. The Digital Power China (DPC) research consortium, consisting of European engineers and China scholars, provides valuable insights in its new report. I am the founder and chair of the iniative.

Read the full report here and the Executive Summary below.

Executive Summary: "Reverse dependencies" DPC Report 2024

This report uses 12 case studies to analyse reverse dependencies of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the European Union and the United Kingdom. In adapting to growing geopolitical competition over digital technology, the EU and the UK are striving for economic security and technological sovereignty. European policies focus on reducing critical over-dependencies on China. This de-risking is a necessary process of adaptation to the new geopolitical realities. The previous Digital Power China report contributed to this policy objective by differentiating between diverging risk profiles across several emerging and foundational technologies, and proposing concrete policy instruments.

However, current de-risking policy ignores the fact that it is virtually impossible to reduce strategic dependencies to a degree that provides the economic security and technological sovereignty the EU and the UK seek. The cost of such decoupling would be enormous and, for good reason, nobody is realistically willing to pay such a price. Technological ecosystems are based on a highly transnational division of labour and all actors are likely to remain interdependent for the foreseeable future. China’s technological advancement continues to rely on the outside world, including Europe.

Under these circumstances, Europe should complement its policy with policies that help to maintain reverse dependencies and keep it technologically indispensable to China. Each technological ecosystem requires a different mix of policies that aim for “autonomy” or “strategic entanglement”. However, reverse dependencies on China should be more prominently factored into European policy.

It is arguable that the logic of interdependence has not prevented Russia from violating international law and attacking Ukraine. Indeed, the high technological and economic costs are no guarantee that the PRC will not act against European core interests. For this reason, Europe must reduce its strategic dependencies on China, as it is currently doing. However, in the absence of a feasible decoupling strategy, maintaining a high cost for China is the best of all imperfect policy options to complement – rather than replace – efforts to reduce strategic dependencies. The PRC is in the middle of a structural economic transformation and economic growth is still considered vital for the legitimacy of the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Security considerations are gaining in importance relative to economic development, but this does not mean that the Chinese leadership does not consider a further deterioration in economic growth to be a threat to its power. In other words, while no guarantee, imposing economic and technological cost still has a fair chance of shaping the considerations of the CCP leadership.

In 12 concrete cases, this report assesses Europe’s technological strengths and the potential leverage they might carry. The character of European technological indispensability, the degree of leverage and mechanisms for utilising this, as well as the policies that Europe should put in place all vary across the technological areas analysed in this study. However, seven patterns can be discerned across all the cases. These are summarised below.

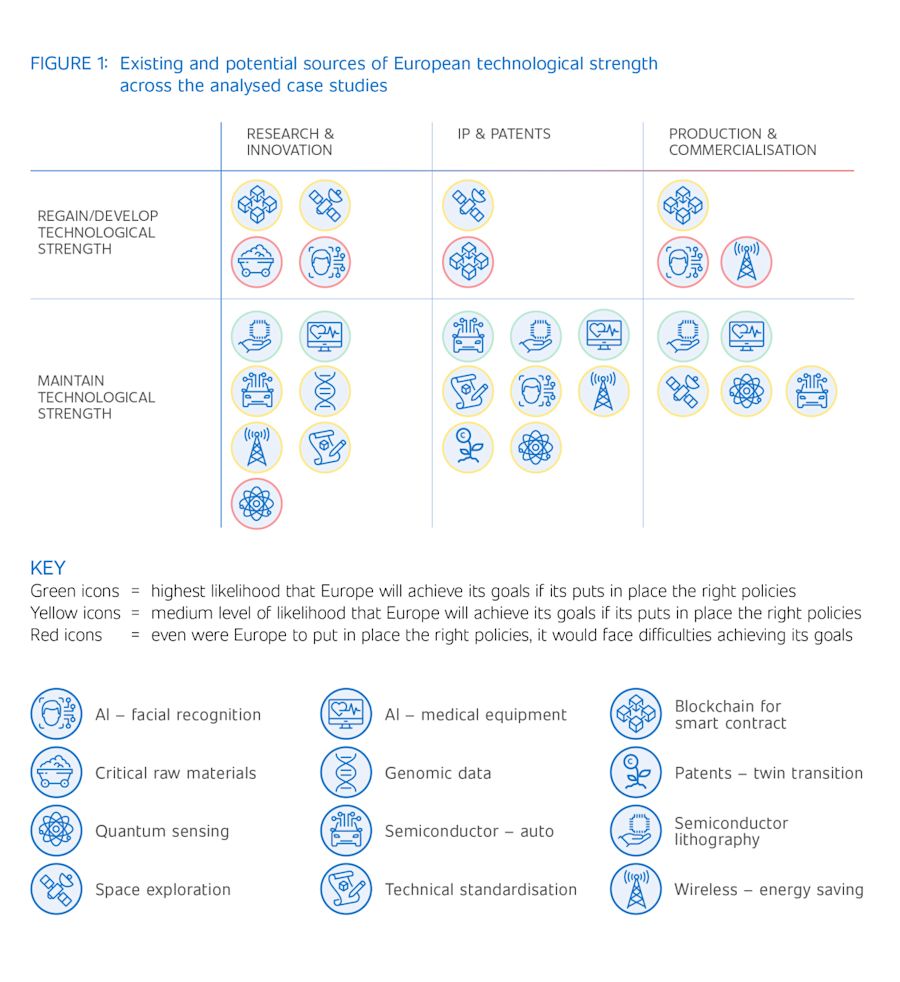

Finding 1: Europe’s greatest source of strength is research and innovation, but intellectual property and production contribute too

Across the case studies analysed, European strengths result from excellent research and innovation, intellectual property (IP) and patents or the production and commercialisation of the respective technologies. In many cases, Europe’s potential leverage results from a combination of these sources. In some cases, Europe is well-placed to develop or regain technological strength in one or several of these three dimensions. In others, the EU should strive to maintain and consolidate the technological edge it already has (see Figure 1).

It is widely known that Europe’s technological capabilities are stronger in research and innovation than in IP and production. However, the cases illustrate that this general finding on European research and innovation strength does not preclude technological excellence in critical niches resulting from IP and commercial products. European strategic indispensability, if achieved, will emerge from a combination of all three pillars.

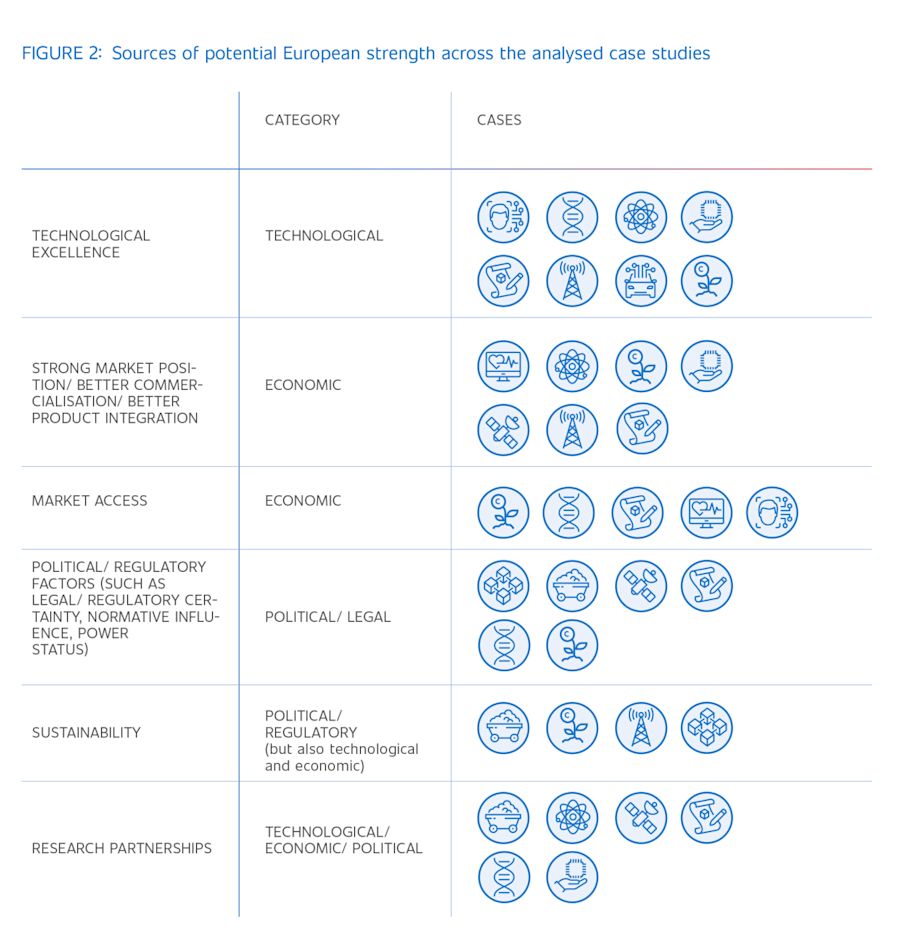

Finding 2: Technological superiority, as well as commercial, political and regulatory aspects, are all decisive factors in European technological indispensability

European technological strength is the result of more than just technological excellence. Depending on the technology ecosystem, economic factors such as a strong market position, better commercialisation conditions, integration of a technology into products or access to the European Single Market play a decisive role. Further factors will be political and regulatory conditions, such as legal certainty, Europe’s normative power or its prioritisation of the sustainable development of technologies. In some cases, a combination of technological, economic and political factors has resulted in technology partnerships that provide a European edge over China (see Figure 2).

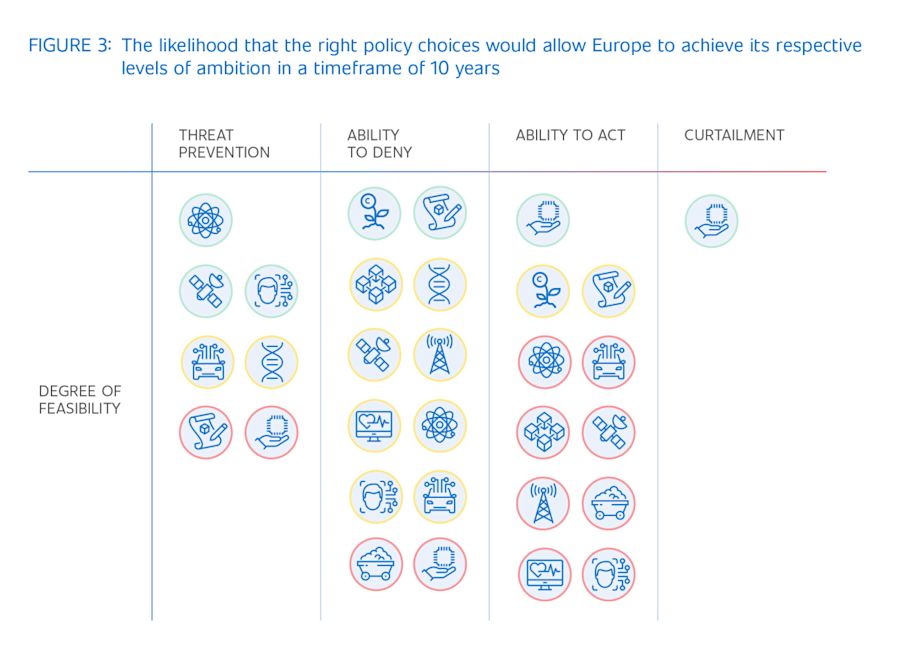

Finding 3: Europe should calibrate its levels of ambition by technology

When considering technological indispensability and the resulting chokepoints, observers automatically think of China’s reliance on European advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment. This hard chokepoint, often associated with the Dutch vendor ASML, is a unique case of a complex technological ecosystem relying on a broad range of mostly European suppliers that it is almost impossible to replicate. No other hard chokepoint of the same quality exists in the digital technologies analysed.

Accordingly, Europe will need to adjust what it is striving to achieve. The level of ambition must vary depending on feasibility and the concrete technological ecosystem. However, the level of ambition is also a matter of political will. Europe needs to calibrate its level of ambition and be realistic about what it can achieve, and what it is seeking to gain politically from a given or potential technological strength. At least four levels of ambition can be distinguished:

Level 1: Threat prevention aims to increase European security by preventing dual-use technology leakage to China, defined along the lines of the Wassenaar Arrangement and the EU dual-use export control regulation (2021/821), or the UK’s Export Control Act 2002 (ECA 2002) and the associated Export Control Order 2008, SI 2008/3231.

Level 2: The ability to deny is about maintaining or creating co-dependencies that constitute a high degree of economic cost for China if Europe were to leverage its strength by means of technological disentanglement. This level of ambition follows a defensive logic as Europe is simply seeking to prevent China from acting against core European interests.

Level 3: The ability to act is more proactive in that it strives to maintain an edge over China. The ability to act is not purely defensive. Instead, it represents a degree of Chinese technological reliance on European strength that allows the EU to shape technological development and related policy directly or indirectly through third markets.

Level 4: Curtailment is about preventing the respective other from developing certain economic and technological capabilities far beyond the security realm. The goal is to limit or freeze Chinese technological and economic development more broadly.

Of the analysed cases, curtailment is only feasible in lithography. Other levels of ambition are achievable, however, depending on the technological ecosystem. Figure 3 summarises the likelihood that the right policy choices would allow Europe to achieve the respective levels of ambition in the analysed cases. The colour code indicates the likelihood that Europe could achieve the respective level of ambition within a timeframe of 10 years if the right policies were put in place. Where an icon is not displayed in a respective box, this level of ambition is not feasible.

Finding 4: Not every European technological strength carries the same degree of political leverage

Technological strength is a necessary but not a sufficient precondition for European leverage over China. Whether Europe can leverage a given technological strength depends on a number of factors, such as ethical considerations, the degree of difficulty substituting the respective technology and the degree of damaging spillover, among other factors. Figure 4 summarises the degree of leverage across technology ecosystems.

Finding 5: Integrate strategic and commercial considerations for a durable technology policy

To a large extent, Europe’s technological strength is the strength of commercial actors alongside publicly funded research institutions such as universities. It is in Europe’s strategic interest to maintain and further develop these strengths in order to retain leverage. A durable strategy means providing a conducive environment for commercial actors to flourish. However, commercial actors do not necessarily consider strategic priorities to a sufficient degree.

Strategic objectives can also become commercial opportunities. For example, even when the uneven playing field of commercial competition between the EU and China puts European market actors at a disadvantage, if competition is solely or mostly over price, the creation of markets for trustworthy technologies can create commercial opportunities.

Europe should develop its technology policy from the starting point that it is unavoidable that companies and consumers will have to pay a premium to cover growing geopolitical risks in the medium term. EU and UK policy must start from the objective of reducing this inescapable additional cost in the medium term. Thus, in the triangle of “promote”, “protect” and “partner”, promote and partner tools that take technology markets into consideration require at least as much attention as protect instruments. Furthermore, such a policy should be framed as an attempt to reduce broader societal insecurity over European economic and technological development and as an explicit attempt to increase societal cohesion and trust.

Finding 6: Balance strategic entanglement and autonomy as two elements of achieving European security

Having identified that dependence on a foreign supplier of critical technology poses a security risk to Europe, the next step is to identify the degree to which this risk can be addressed through entanglement (indispensability) or autonomy.

If European and Chinese technology suppliers are entangled in a critical technology ecosystem, Europe’s long-term policy objective should be to ensure or achieve indispensability within entanglement. The goal should be for European technology to play an indispensable role in the Chinese technology ecosystem. Strategic entanglement creates security through indispensability; targeted reverse dependencies keep the cost of conflict very high for China.

Autonomy reduces dependence and vulnerability in Europe and thereby increases European security, but a technologically independent or self-reliant China also poses security challenges for Europe.

This distinction does not ignore the fact that there will still be credible economic interactions between the EU and China that do not fall into the category of strategic entanglement. However, the objective of this study is to identify under which circumstances, how much and what kind of interaction with China can increase European security, or when autonomy should be the strategy of choice. Autonomy and strategic entanglement are two poles on a continuum and need to be properly balanced. This balance will vary across technology ecosystems but also depend on the level of European ambition, as outlined above.

Finding 7: Policy recommendations for Europe are technology-specific and vary according to level of ambition, from research promotion to knowledge security and commercialisation

European policy on developing or maintaining technological indispensability in critical technological niches requires case-specific policies. No one-size-fits-all approach can provide conducive conditions for, let alone a guarantee of, retaining technological indispensability.

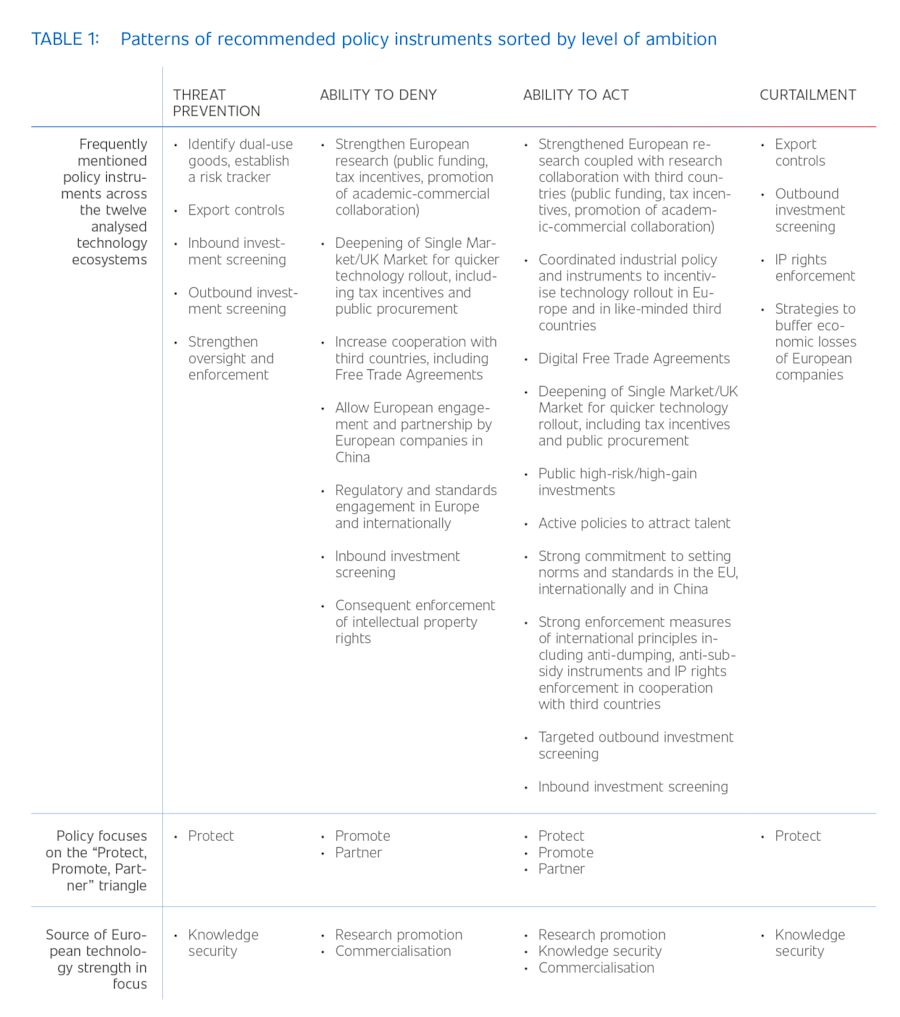

The comparison of the analysed cases does illustrate, however, that policies vary depending on level of ambition. A comparison of the policy instruments proposed for the four respective levels of ambition finds several patterns, which are summarised in Table 1.

That is not to say that all of these instruments are crucial in all cases, and instruments not mentioned in this list can also be important in individual technology ecosystems. European policymakers must not neglect the specific characteristics of different technology ecosystems.

European policymakers need to balance protective measures with openness towards China. For example, outbound investment screening to prevent the export of innovation capabilities from Europe to China can be useful not only in a narrow security context, but also as a factor in preserving European competitiveness. However, in isolation, outbound investment screening will not resolve Europe’s challenges. “Promote” and “partner” tools are the most crucial instruments and strengthening Europe will be essential. Targeted “protect” measures can help, but will not resolve Europe’s problems. A further challenge will be for policies to remain technology agnostic and avoid the trap of simply protecting incumbents. European policy responses must adequately address geopolitical challenges, remain economically viable in the environment of European free market economies and take account of specific emerging or foundational technologies.

Read the full report here

About the Digital Power China Research Consortium

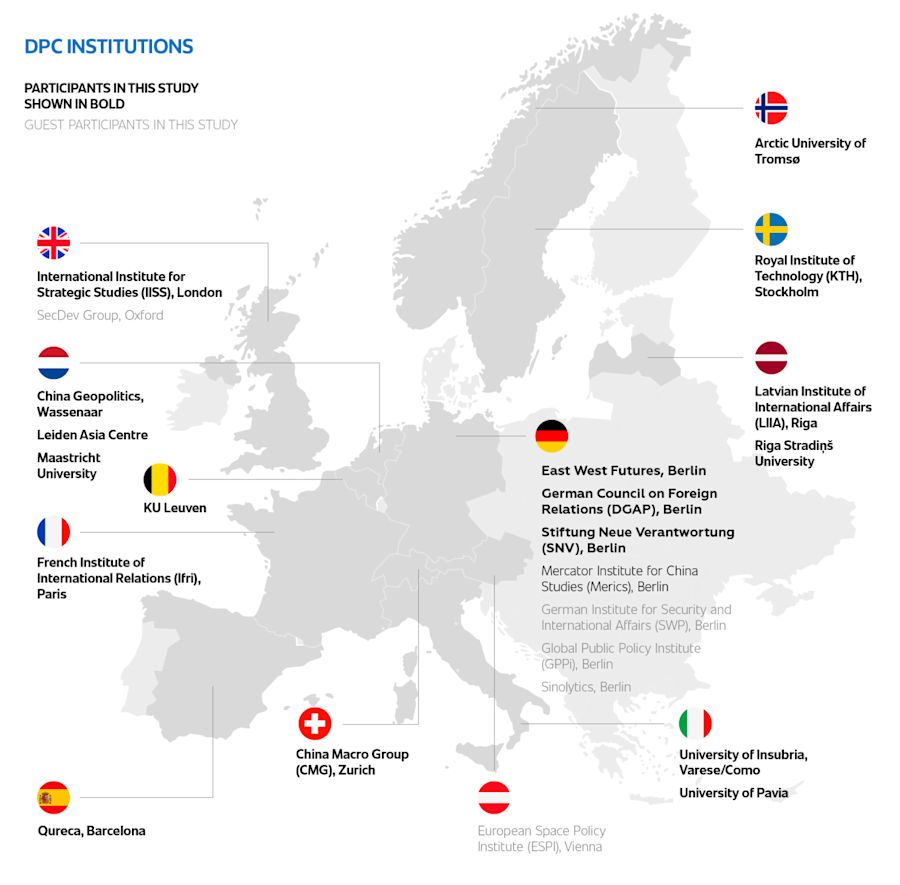

The Digital Power China (DPC) research consortium is a gathering of 21 China experts, economists and engineers based in 12 European research institutions, universities, think tanks and consultancies in 10 European countries. Not all DPC researchers contribute to every report. For this report, DPC has been joined by invited guest researchers.

The group is devoted to tracking and analysing China’s growing footprint in digital technologies, and the implications for the European Union. DPC offers the EU concrete policy advice based on interdisciplinary research. I am the convenor of DPC.

DPC systematically pairs technological and country expertise, which is based on rigorous academic research combined with experience of the provision of policy advice. The informal group brings together a variety of European researchers in order to combine diverging perspectives from across the continent. Responsibility for the accuracy of the views expressed remains solely with the indicated authors.

This report has been generously funded by the United Kingdom’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, and the China Knowledge Network (CKN) of the Government of the Netherlands, with support from the EU Cost Action “China in Europe Research Network” (CHERN).

We would like to thank Andrew Mash, who has edited this and all previous reports and papers published by DPC for the exceptional cooperation.

Related videos

More publications by the Digital Power China research consortium

2022: Assessing China's Digital Power and its Implications for the EU. Berlin: Digital Power China.